The U.S. just grew by 1,000,000 square kilometres

The Global Race for Critical Minerals heats up

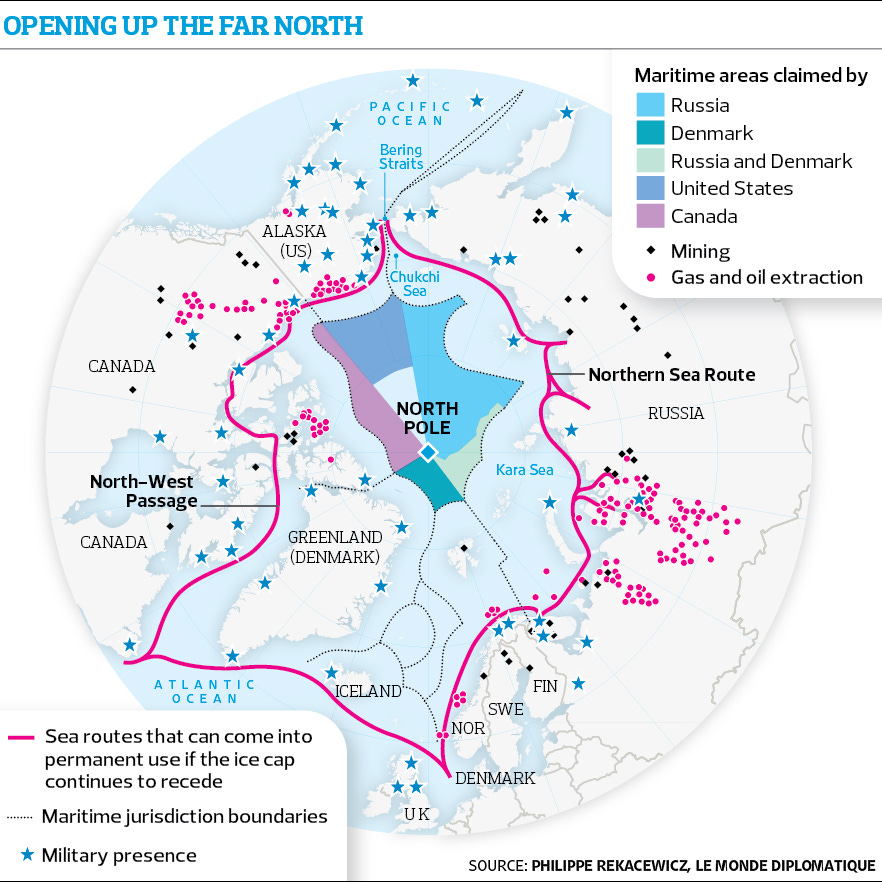

The new era of geo-economics has arrived, and the race for strategic minerals in the new clean energy industry is upon us. The United States has just made a territorial claim of real significance, expanding their territory by over 1 million square kilometres, an area about twice the size of California or half the size of the Louisiana Purchase. They have for the first time declared the outer limits of their extended continental shelf (ECS), the portion of its coast beyond 200 nautical miles (nm) which would grant them authority over large swathes of the Arctic Ocean surrounding Alaska. This declaration comes after the International Energy Agency reported that for the first time, global demand for fossil fuels will peak or plateau as the world transitions to renewable energy and “clean technologies” predicated on critical earth minerals. These developments have important political implications in the short and long-term, and they underscore a key area of geopolitical tension that could define the 21st century, a race to exploit natural resources through deep-sea mining, between all nations big and small, to see who will dominate the key commodities of our new technological age.

You may be thinking, how does a country simply claim a new tranche of land this size? Well, it is an exercise in scientific and legal prowess that such a feat can be pulled off, and it shows how strategically, the United States is making big moves in order to slow down the rapid decline of U.S. hegemony. First, in order to understand this territory claim, we have to understand the international laws governing maritime borders, the scientific research behind the discovery continental shelf margins, and the geo-economics of the strategic minerals industry. So, let’s begin.

Laws of the Sea

Territorial waters are categorized into distinct zones with each zone conferring different rights and opportunities to a coastal state. These current maritime zones are outlined under the third United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III), a monumental treaty ratified in 1994 by the majority of the world’s nations. Under the provisions of UNCLOS, “the sovereignty of a coastal state extends beyond its land territory… to an adjacent belt of sea described as the territorial sea.” The territorial sea extends up to 12 nautical miles from the coastal states baseline, and the state exercises sovereignty over these waters, which includes everything from air space above down to the seabed and the subsoil beneath it. The adjacent belt of sea extending from 12 nm to 24 nm from baseline is known as the contiguous zone. In this territory, a state has jurisdiction over the ocean’s surface and seabed, but not the airspace. They can enforce their own customs, including sanitary regulations or immigration laws, but they do not have the same control over this area as they do the territorial sea.

Finally, we have the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) which extends up to 200nm off the coastal state’s baseline. The state has sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring, exploiting, managing, and conserving natural resources on the seabed and the subsoil, just like in its other maritime zones, however, they do not have the right to enforce customs and laws like they do in the areas up to 24nm from their coastline. As the name suggests, the EEZ essentially allows the coastal state to legally conduct full economic exploitation of the area. In addition to this it awards them primacy regarding marine scientific research and the ability to construct installations such as artificial islands and other structures like oil rigs, as permitted under international law. Now there are plenty of conditions that can alter the delineations of these outer zones such as when two countries’ territorial waters intersect requiring bilateral agreements, but the important thing is to understand the basis of these maritime boundaries and the rights that each zone confers.

UNCLOS not only clarifies the rights and responsibilities of coastal states in these different maritime zones, but it also established the legal basis for defining the continental shelf. It is defined as the “natural prolongation of the land territory on the continental margin’s outer edge” or 200nm from the baseline whichever is larger. The continental shelf can extend up to 350 nm from baseline depending on these circumstances and states can harvest minerals and other non-living materials in the subsoil of its continental shelf, to the exclusion of others. It should be clear now why states invest so much into the research and litigation behind the extension of their maritime boundaries. The rights to mine these areas are monumental.

The collaboration on the UNCLOS treaty has helped regulate the seas and has been essential for mediating conflict in highly contentious territorial disputes. Given that the international community has an interest in preserving the marine environment as well as maximizing economic opportunities, there needs to be a balance between territorial claims over areas rich in natural resources, and environmental regulation of deep-sea mining that encourages sustainable practices and avoids ecological setbacks. Both of these concerns are addressed in UNCLOS.

The economic side of this is addressed under the concept of Sovereign rights over Natural Resources. In our current economy, strategic minerals are paramount, and hydrocarbon resources like oil and gas are fundamental commodities for a nation’s energy infrastructure. Each nation is privy to the exploration and excavation of natural resources within their continental shelf boundaries, making the definition of this zone vital to the functioning of a state’s economy. Responsibilities relating to Environmental protection and Conservation require nations to reduce pollution and ecological risks posed by natural resource excavation in order to protect marine ecosystems in their territory. This balancing act keeps nations in check and fosters international collaboration on new technologies for sustainable mining practices while allowing sovereign states to exploit the resources in their jurisdiction.

The U.S. and UNCLOS

This is all well and good. However, geopolitical competition arises especially from claims over what is known as the extended continental shelf. This is due to the fact that the ECS, while outside of the EEZ, still bestows exclusive mineral rights to the coastal state in question and can stretch up to 350 nm from baseline. Exclusive fishing rights however are not included in the ECS zone. So, this brings us to the U.S. and their new territorial expansion claims. While territorial demarcations are clearer up to the continental shelf, extended continental shelf claims must be submitted to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) which is an arduous process, where meticulous and rigorous scientific research is required to build a case that meets the criteria for the ECS under Article 76 of UNCLOS.

By analysing bathymetric, seismic, and geomorphological factors, scientists illuminate the geological structure of the continental margin and its relationship to the seabed’s topography, using this data to substantiate their legal claims of expanded jurisdictional rights. This symbiotic relationship between science and law were essential to the U.S. territory claim. The ‘US Continental Shelf Task Force’ spearheaded the research which included 14 different federal agencies beginning in 2003 and costing tens of millions of dollars. Four of the five Arctic Ocean coastal states, Denmark (via Greenland), Russia, Canada, and Norway have already made at least one submission to UNCLOS, which really demonstrates how important it was that the U.S. acts sooner rather than later in delineating their continental shelf boundaries.

It is important to note that the U.S. has still not ratified UNCLOS. Ronald Reagan originally praised many of the treaty’s provisions, but he objected to ratification on the grounds that the Convention would restrict or impede U.S. rights to deep sea mining. Senate Republicans have traditionally been averse to multilateral institutions, an ideological position that is inextricable from the Reagan administration’s original objection, predicated on the idea that U.S. industries should not be restrained by any international regulatory system. The Senate needs a 2/3 majority vote to ratify the treaty, but subsequent administrations could not win enough Senate seats to override this philosophy against multilateral agreements. The bill rarely even reached the Senate floor because of this opposition.

Republican Senator and chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during the Bush administration, Richard Luger, lamented this fact after strong support from Senators and U.S. industry representatives like the American Petroleum Institute (API) was not enough to get the treaty vote on the calendar in 2004. Luger blamed the “vague and unfounded concerns about the Convention’s effects, primarily by those who oppose virtually any multilateral agreement because of ephemeral conservative concerns that boil down to a discomfort with multilateralism.” Lobbying efforts continued to entrench this position within the Republican party, restricting the Obama administration from voting on UNCLOS.

In 2014, Obama criticised the Senate for not ratifying the treaty. And this was during a period when the US was debating how to respond to China’s increased aggression in the South China Sea. Obama stated that “It’s a lot harder to call on China to resolve its maritime disputes under the Law of the Sea Convention when the United States Senate has refused to ratify it.” The domestic politics surrounding ratification of UNCLOS is important because while the U.S. is somewhat adhering to the Convention by way of their recent announcement, they still technically are not confined to the boundaries of mining and resource exploitation prescribed by this particular UN treaty, which may have unknown geopolitical ramifications in the future if UNCLOS continues to avoid ratification in the Senate, or if UNCLOS members feel that they have rights to the same territory. Even the State Department’s announcement regarding the ECS was a unilateral one, involving some specific phrasing, stating that they have “prepared” a submission to the CLCS, which they of course cannot officially file until they ratify the Law of the Sea Convention and become a member state. They have however said that they are open to filing the submission as a non-party to the Convention, which seems like a way to circumnavigate the need to ratify the treaty in the first place. If the regulatory purposes of UNCLOS are based on the idea that all countries abide by the same binding international laws, accepting America’s submission without them adhering to the treaty would seriously undermine the Convention’s legitimacy. If submitted, the review will not take place for decades either way due to the volume of submissions around the globe, but for now, it is a step towards protecting their territory rights and future economic opportunities.

Global race to define ECS

Now, it’s not just the United States making these kinds of moves. With the rapidly increasing value of critical minerals in the 21st century especially, coastal states have made it an imperative to employ scientific task forces to conduct surveys of their seabed and define their continental shelf boundaries before their neighbours do. In 2016 for example, Argentina attempted to define their continental shelf on the back of their own scientific research. The original submission to the CLCS included claims to the ECS around the Falkland Islands, South Atlantic Islands, and some Antarctic territory, which would have allocated an additional 1.7 million square kilometres to the Argentine government. However, these claims were unsubstantiated, eventually being deferred by the CLCS because of the sovereignty dispute over the Falkland Islands. Both the UK and Falklands governments rejected the claims in addition to the Chilean government who downplayed the validity of Argentina’s aspirations. Their claims to Antarctic territory also contravene aspects of the Antarctic Treaty, and Chilean officials emphasised this in their response to the submission. Argentina was only able to get the CLCS to substantiate continental shelf claims in the undisputed areas, amounting to 1,633 square km gained, a meagre development compared to the 1.7 million they were aiming for. Chile, the UK, and Argentina will all attempt to expand their territories in this region where their jurisdiction claims intersect, making competition for deep sea mining rights a primary source of geopolitical tensions for these countries going forward.

Last year in 2023, Nicaragua was also dealt a blow regarding ECS claims in the Caribbean Sea surrounding the islands of San Andres and Providencia (Figure 2). The area is said to be rich in oil and natural gas, but the extension would have infringed upon Colombia’s continental shelf up to 200nm, which is why the ICJ ruled in Colombia’s favour. These are just some of the many labyrinthine disputes and resolutions that revolve around the continental shelf.

The race for resource exploitation on the seabed and its subsoil is heating up all around the globe and the successful claimants will reap the rewards if they can justify their assertions along the intricate and stringent parameters of UNCLOS. Portugal also made a high-profile submission to the CLCS back in 2009, for which the legal process is still ongoing, laying claim to over 2 million square kilometres which would double its territory, making it one of the largest countries in the world, although only a tiny fraction of it being land. Under the Mar-Portugal action plan, Portugal intends to enhance their soft power in the Atlantic with this new territory. The archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores are key to their claims. If their submission is successful, they will seek to construct new facilities for communications, scientific research, new shipyards, ports, and much more. The new ports would be capable of receiving large international cargo carriers, reinforcing Portugal’s role in the key global shipping networks than run through their EEZ. And this is to say nothing about the alleged mineral rich soils of the Mid Atlantic Ridge near the Azores archipelago. These are the kind of economic advantages that ECS claims can provide, and the importance of these developments cannot be overstated. It is clear from America’s ECS demarcation that they are planning to dominate the Arctic seabed around them, not unilaterally as there has been plenty of multilateral cooperation between the Arctic Ocean states, but they will nevertheless control a meaningful portion of the seabed under the new boundaries.

Economic and Strategic Opportunities of Territorial Expansion

A wide array of economic and strategic possibilities has been opened up with this additional territory. New technological developments will be needed before they can exploit these areas, but the new borders will allow the US to protect potentially lucrative seabed territories for future exploitation. As the Arctic ice melts due to rising global temperatures, new areas of exploration become available that were previously inhospitable to industrial occupation. Of course, even within a given Arctic state’s own jurisdiction, all out economic exploitation isn’t realistic given the fragile ecological situation in the region. International agreements and councils, such as The Arctic Council, epitomize the diplomatic and scientific cooperation behind the environmental preservation of the Arctic. These initiatives again demonstrate the complicated web of legal frameworks that underscore the exploitation of shared maritime spaces. Regardless, economic opportunity, particularly in relation to critical minerals will be a primary goal of the US as they attempt to create an internal supply chain of the essential commodities for our modern technologies.

Critical Minerals and Natural Resources

The Biden administration has made domestic research and manufacturing of semiconductors a central tenet of their regime. The US Chips and Science Act was passed in 2022 with one fundamental goal. It is industrial policy pertaining to semiconductor manufacturing on U.S. soil, intended to help the US wean themselves off of China’s abundant mineral resources as well as compete with their semiconductor industry. Enormous subsidies of $280 billion were authorized as the US strives to control as much as they can domestically when it comes to the green technologies industry. As the era of globalisation comes to an end, and new security conflicts manifest all around the globe, a turn towards protectionism, first under Donald Trump and even more so under Joe Biden has characterized the United States’ economic policy in many respects. The less trust and cooperation between the U.S. and China, the more the Americans pull back from economic intercourse with the Chinese, even though the macroeconomic policies of hyper liberalised markets and rapid globalisation were a key factor in the economic proliferation of both countries, as well as other states, over the past few decades.

Perhaps, the semiconductor industry and acquisition of critical minerals is best kept domestic, given the enormous importance of having a secure supply chain of these resources in a world where our most fundamental technologies rely on their availability. Everything from smartphone and electric vehicle batteries to solar panels and military technologies like radar require minerals like lithium, cobalt, chromium, copper, manganese, germanium etc., all of which will only grow in demand as industries transition to clean energy sources in order to appease global calls to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. China is leading the field in the terrestrial mining of these minerals and therefore dominates the semiconductor industry. If the U.S. is lucky enough to discover nodules of critical minerals within their newly claimed territory, it will be a huge boost to their clean energy transition and their goal of independence from China in this particular sector. Seeing as US independence in the semiconductor industry is a key national security concern for the Biden administration, the ECS research and announcement highlights their strategic interest in securing these hard minerals and keeping China’s steady rise to global dominance at bay.

The natural resource benefits of this new expansion are not only based on these strategic minerals. At the present moment, oil and gas are still king in the global energy market and the Arctic has a vast untapped potential when it comes to these precious commodities. The US Geological Survey estimates that the Arctic Circle may contain over 90 billion barrels of oil and 30% of the planet’s undiscovered natural gas. The ECS limits outlined in the United State’s executive summary includes an area that extends 350 nm north of Alaska’s baseline in addition to parts of the Bering Sea to the West. After some high-profile oil spills in the Arctic including the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 in Alaska and the Norilsk oil spill in 2020 in Russia’ Arctic territory, it would be prudent to apply serious regulatory measures before a massive uptake in drilling practices within America’s new ECS boundaries. But considering the financial incentives of these metaphorical goldmines, America will be eager to take advantage. This graphic (below) shows the deposits of oil and gas, along with exploration and extraction sites in the Arctic. Each Arctic nation would love a bigger slice of the pie.

No official bilateral agreement has been established between the US and Canada regarding their intersecting Arctic territories, and the US ECS boundaries overlap with Canada’s own potential claims. If a rich oil or gas deposit is discovered in the overlap zone before a bilateral agreement is achieved it could be an area of geopolitical apprehension for the North American states. Energy competition is a fundamental aspect of geopolitical relations, and the recent US territorial claims are indicative of this constant struggle.

National Security Opportunities

Exploration of this new land is needed in order to devise a comprehensive strategic framework for the region’s future. Possibilities range from undiscovered marine life, energy and mineral reserves, and even new routes for fibre optic cables across the world. These are the possibilities associated with rights to the seabed. But beyond these economic possibilities the security strategy of the United States has been liberated in this area. Airplanes, satellites, and other forms of policing could be implemented. Two Congressional hearings in December 2023 alone have been pushed for new US polar icebreakers, indicating that a plan for infrastructure development there is under way. Part of the United States National strategy for the Arctic between 2022-2032 is to invest in infrastructure, such as the development of a deep draft harbour in Nome, as well as small ports, airfields, and other structures in consultation with the state of Alaska and its Indigenous communities. Beyond these investments, the projection of US power and fortification of their military presence in the Arctic is the first pillar in the Executive Summary of their Arctic Strategy. They have clear National Security initiatives from improving communications and navigations capabilities, to working with Canada on projects like the modernization of the North American Aerospace Defense Command. They also outline a desire to increase their focus on combined exercises with NATO allies in the Arctic Region in order to “maximize unity” during a time of great “tension with Russia.” These initiatives are all outlined in their new Arctic Strategy and the ECS claims are clearly part and parcel of these developments. Growing geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and East Asia have pushed America to act now with regards to developing all aspects of its national security and economic opportunity.

Geopolitical implications for International Community

Finally, its necessary to mention the potential response from the international community regarding the US decision to unilaterally claim land. Apart from the proximal concerns like mining disputes with Arctic neighbours, the precedent that this sets for other superpowers, namely China, is problematic. Yes, China will not be thrilled by Americas continuing push to secure their own mineral supply chains, but worse than this is the fact that if the US acts unilaterally in their territorial expansion, China can justify the same moves for themselves. They can continue the construction of islands, and other tactics to strongarm their way to victory in their own territorial disputes with countries like Viet Nam, Japan, and the Philippines in the South China Sea. If the US is paying lip service to UNCLOS with their new declaration but in reality, not abiding by the provisions of the treaty because they are not a party member, there is nothing stopping China from violating UNCLOS by engaging in aggressive territorial expansion in their own region where the balance of power is in their favour. Just as Obama said nearly a decade ago, it is difficult to justify a condemnation of China’s tactics in the South China Sea when the US hasn’t truly acquiesced to the UN’S Laws of the Sea themselves.

In the end, the stated desire to submit an ECS claim to UNCLOS even as a non-member could indicate a shift for the US towards acceptance and ratification of the treaty. Conversely, it could be a ploy to maximize their territorial rights without officially being subservient to the multilateral regulations that everyone else is playing by. Either way, some critical strategic benefits will be available to the US in the near and long term with this new territory, but only time will tell how accepting the international community, or more importantly their geopolitical rivals, will be of the decision. It may justify unilateral territorial claims by rival powers like China, which would be an inauspicious development in international politics. For the moment, the only definite result is that the inevitable US expansion train rolls on, and there’s no indication that this is the last stop.